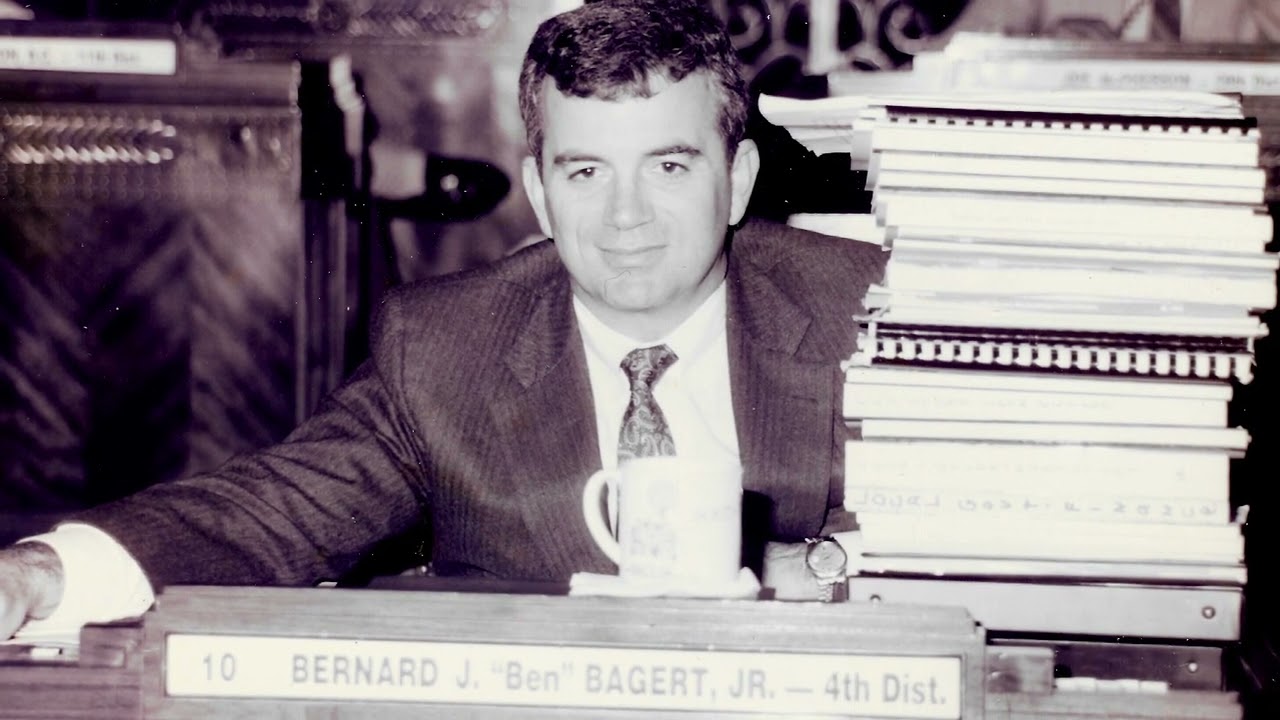

Ben Bagert has been inducted to the Louisiana Hall of Fame.

In the News:

2019 voted a “Top Lawyer” – Bernard J. Bagert

2019 voted a “Top Lawyer” – Gregory Ernst

CRIMINAL LAW: Sentencing—Apprendi Applies to Criminal Fine

CRIMINAL LAW – Retroactivity of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010

U.S. Supreme Court decides GPS case in favor of defendant

Honest Services – U.S. Supreme Court limits prosecutor tool in fraud cases

Fair Sentencing Act – Congress acts to reduce sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine

Rated One of New Orleans’ Top Lawyers

January 6th, 2010

The New Orleans Magazine listed Ben Bagert as one of

New Orleans’ Top Lawyers in the November 30th edition,

2009

The Rules of Government Regulatory Boards and Agencies Are Often Out of Bounds

We have assisted clients with Government regulatory boards and agencies that exceed their legal authority when adopting and enforcing rules and regulations. Spurious bureaucratic fiats often involve efforts to:

- Deny or restrict business or professional licenses.

- Enforce burdensome practices and behaviors by businesses or professionals.

- Require the purchase of unnecessary and expensive equipment or insurance.

- Restrict access to the free market place.

Government rules and regulations are sometimes illegal under the Constitution, the statutes that created and empowered the agency, and the Administrative Procedure Act. In many cases the Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeal have enjoined government agencies from enforcing regulations when they have exceeded the authorization delegated by the legislature that empowered these agencies in the first place. These Courts have further explained that government agencies are not free to pursue any and all ends – their power is limited to those ends that are connected to the task delegated by a legislative body.

CRIMINAL LAW: Sentencing—Apprendi Applies to Criminal Fine

The Lawletter Vol 37 No 4

Mark Rieber, Senior Attorney, National Legal Research Group

The Supreme Court has extended the rule in Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000). Apprendi held that the Sixth Amendment reserves to juries the determination of any fact, other than the fact of a prior conviction, that increases a criminal defendant’s maximum potential sentence. In Southern Union Co. v. United States, 132 S. Ct. 2344 (2012), the question presented was whether the same rule applied to sentences of criminal fines. Southern Union, a natural gas company, was convicted of violating a federal statute, 42 U.S.C. § 6928(d)(2)(A), by knowingly storing liquid mercury without a permit. The jury verdict form stated that Southern Union was guilty of unlawfully storing liquid mercury “on or about September 19, 2002 to October 19, 2004.” 132 S. Ct. at 2349. Violations of the statute are punishable, inter alia, by “a fine of not more than $50,000 for each day of violation.” 42 U.S.C. § 6928(d)(2)(A). At sentencing, the probation office set a maximum fine of $38.1 million, on the basis that Southern Union had violated the statute for each of the 762 days from September 19, 2002 through October 19, 2004. Southern Union objected that the calculation violated Apprendi because the jury had not been asked to determine the precise duration of the violation. Further arguing that the verdict form and the court’s instructions permitted conviction if the jury found even a one-day violation, Southern Union maintained that the only violation the jury necessarily found was for one day and that imposing any fine greater than the single-day penalty of $50,000 would require fact finding by the court, in contravention of Apprendi. While acknowledging that the jury had not been asked to specify the duration of the violation, the Government argued that Apprendi did not apply to criminal fines.

The district court held that Apprendi applied, but it concluded from the verdict that the jury had found a 762-day violation. The court therefore set a maximum potential fine of $38.1 million and imposed a fine of $6 million and a community service obligation of $12 million. On appeal, the First Circuit rejected the district court’s conclusion that the jury had necessarily found a violation of 762 days, but it affirmed the sentence, holding, in conflict with other circuits, that Apprendi did not apply to criminal fines.

The Supreme Court reversed the First Circuit and held that Apprendi did apply to criminal fines. The Court stated that it had applied Apprendi to a variety of sentencing schemes involving imprisonment or a death sentence and could see no principled basis under Apprendi for treating criminal fines differently. The Court also rejected the Government’s argument that fines are less onerous than incarceration and the death sentence and thus do not implicate the primary concerns motivating Apprendi. Not all fines are insubstantial, however. Moreover, the relevant question is the significance of the fine from the perspective of the Sixth Amendment’s jury trial guarantee. “Where a fine is substantial enough to trigger that right, Apprendi applies in full.” 132 S. Ct. at 2352. The Court remanded the case for further proceedings.

CRIMINAL LAW – Retroactivity of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010

The issue of whether to apply a new sentencing law to crimes committed before the enactment of the law has long confounded judges, both because of the recurring failure of legislatures to be clear about their intentions and because of the inherent questions of fairness that arise from the imposition of disparate sentences for the same crime simply by reference to a date on a calendar. The resolution of such issues often boils down to the weighing of both of those factors and a determination of which one is more significant in the case before the court.

Concerns about fairness prevailed over equivocal evidence of the intent of Congress when a divided U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled that the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which dramatically reduced the disparity in length of sentences for offenses involving crack cocaine rather than powder cocaine from a ratio of 100 to I to a ratio of 18 to I, may be applied retroactively to crimes committed before the law became effective. In Dorsey v. United States, 132 S. Ct. 2321 (2012), Justice Breyer wrote for a five-member majority that allowing vastly different sentences at “the same time, the same place and even [with] the same judge” would result in “a kind of unfairness that modern sentencing statutes typically seek to combat.” Id. at 2333.

In a dissenting opinion for the four-member minority, Justice Scalia argued that I U.S.C. § 109, a law enacted in 1871 and providing that a new criminal statute that ‘”repeal[s]'” an older criminal statute shall not change the- penalties “‘incurred under that older statute'” unless the repealing Act shall so expressly provide,'” id. at 2339 (Scalia, J., dissenting)(quoting I U.S.C. § 109), precluded retroactive application of the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 because Congress did not explicitly provide for retroactive application. However, Justice Breyer and the majority determined that there were sufficient indications, including the way that Congress had instructed the Federal Sentencing Guidelines to be amended, that Congress had meant to have the new law apply retroactively.

-This article was written by Doug Plank, Senior Attorney, National Legal Research Group, Law Letter Vol. 37, No. 3.

U.S. Supreme Court decides GPS case in favor of defendant

In United States v. Jones, 132 S. Ct. 945 (2012), the Supreme Court held that the attachment by police of a Global-Positioning-System (“GPS”) tracking device to a vehicle, and the subsequent use of that device to monitor the vehicle’s movements on public streets, constituted a “search” within the meaning of the Fourth Amendment.

In Jones, police, without a valid warrant, attached the GPS device to Jones’s vehicle and tracked the vehicle’s every movement for 28 days. Holding that Jones had had no reasonable expectation of privacy when the vehicle was on public streets, the trial court denied Jones’s motion to suppress the data obtained, and Jones was ultimately convicted on drug charges. On appeal, the court of appeals reversed, holding that tile attachment of the GPS device to the vehicle and its use to monitor the vehicle’s movements constituted a search.

The Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Scalia, affirmed the decision of the court of appeals. All nine Justices agreed that the surveillance had violated Jones’s rights, but they split on their reasoning. Five Justices however, concluded that the physical act of placing the GPS device on the vehicle constituted a search under the Fourth Amendment.

In a concurring opinion joined by four Justices, Justice Alito stated that in light of all the possible ways of monitoring a person’s movements that do not require a physical intrusion or trespass, he would have analyzed the question presented by asking whether Jones’ reasonable expectations of privacy had been violated by the long-term monitoring of the vehicle he drove rather than deciding tile case “based on 18th century tort law” related trespass. 132 S. Ct. at 957 (Alito, J., joined by Ginsburg, Breyer, and .Kagan, JJ. concurring in judgment).

U.S. Supreme Court limits prosecutor tool in fraud cases

For years federal prosecutors have used the vague “honest services” statute (18 U.S.C. § 1346) as a tool to convict defendants who did not directly obtain money or property. The statute functioned as an expansion of the definition of fraud to include schemes to “deprive another of the intangible right to honest services.”

In Skilling v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court significantly limited the government’s reliance on this favored prosecutorial tool unless the government can demonstrate that the defendant received a bribe or a kickback. As a consequence, the government will no longer be able to use this statute to prosecute white collar cases involving breaches of fiduciary duty and self-dealing under an “honest services” theory where the defendant does not receive a bribe or kickback.

The principle issue in Skilling was whether 18 U.S.C. § 1346 was unconstitutionally vague in denouncing conduct that deprives another of the “intangible right of honest services.” The Court held that the reach of Section 1346 must be confined to cover only those fraud cases in which bribery and kickback schemes are involved. Writing for the Court, Justice Ginsburg stated that “Skilling’s vagueness challenge has force,” but refused to invalidate the statute in its entirety. The Court held that Skilling did not violate Section 1346 because the prosecution did not allege that he solicited or accepted bribes or kickbacks, but instead that he conspired to defraud Enron’s shareholders by other means. Construing the statute very narrowly, Mr. Skilling’s honest services fraud conviction was vacated. The Court left open on remand whether the error was harmless, given the other allegations of fraud. The Court further left open on remand whether reversal on conspiracy would necessitate reversal on other counts.

Justice Antonin Scalia, joined by Justice Clarence Thomas and Anthony M. Kennedy, concurred in part and concurred in the judgment. Scalia reasoned that Section 1346 is unconstitutionally vague and should therefore be struck in its entirety. Justice Samuel A. Alito, concurring in part and in the judgment, stated that the “impartial jury” requirement, set forth in the Sixth Amendment, requires only that “no biased juror is actually seated at trial.” Justice Sonia Sotomayor, joined by Justices John Paul Stevens and Stephen G. Breyer, concurred in part and dissented in part. Sotomayor agreed with the majority’s resolution of the “honest services fraud” claim; however, she disagreed that Skilling received a fair trial based on the hostility that emerged in Houston after the collapse of Enron.

Congress acts to reduce sentencing disparity between crack and powder cocaine

Congress has changed a quarter-century-old law that punished crack cocaine offenders with far greater severity than powder cocaine offenders. The Bagert Law Firm believes that correction of this disparity was long overdue.

The former law (21 U.S.C. § 841(b)(1)(B)), a result of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, was enacted in response to public concern that crack cocaine was especially addictive and inherently caused violence. However, time and technology have proven that the assertions about the differences between crack and powder cocaine were exaggerated and many scientists believe that the two drugs are chemically identical.

Under the former law, a person convicted of mere possession of 5 grams of cocaine base (crack) would receive a mandatory minimum sentence of 5 years in prison which could not be suspended by the sentencing judge. However a person convicted of possessing the same weight of cocaine powder was subject to no more than 1 year in jail and that sentence could be suspended.

Under the new law, simple possession of both crack and powder cocaine are treated the same – a one year maximum imprisonment that may be suspended.

However, even under the new law a penalty disparity remains for those convicted of distribution of crack as compared with powder. Under the old law, the severity ratio between crack and powder distribution was 100:1. For example, a person convicted of distributing only 5 grams of crack was subject to the same minimum sentence as a person convicted of distributing 500 grams of powder – not less than 5 nor more than 40 years without suspension of sentence. Under the new law distribution of 28 grams of crack (instead of 5 grams) will invoke the 5 year minimum sentence.

Federal criminal defense lawyer, Ben Bagert stated: “The new law is a step in the right direction, but Congress still needs to overhaul its sentencing policies for non-violent drug offenders who are serving very lengthy periods of incarceration at great taxpayer expense.

Law Pay Online

Use our easy-to-use and secure online payment feature.

We accept all major credit cards.